Reading Group: Recovering the Intellectual Origins of Technology

Cosmos Institute's first in-person & virtual reading group

Update: This reading group was turned into a podcast using NotebookLM.

Throughout history, major scientific discoveries have transformed how we see ourselves as human beings. Each breakthrough forced us to redraw the map of our place in the cosmos:

Copernicus dislodged us from our central position in the universe

Bacon revealed we could master nature for our purposes

Newton proved the world follows mathematical laws, not human intuition

Darwin situated us within the animal kingdom

Now we're living through another such moment—perhaps the culminating point of the modern technological project: the Age of Turing. As artificial intelligence reshapes our word, we are invited to return to the history of ideas to reconsider the place of technology in human life: what good it produces, what danger it poses, and what should be its relation to human guidance or morality.

Each change in the orientation of intellectual life emerged from a fundamentally optimistic or pessimistic disposition toward technology.

Though the ancients were concerned about technology, their orientation to nature’s apparent limits made them moderates. We moderns are the children instead of an ambitious optimism–of the Enlightenment ideas that we can only know what we design or make and that we can master nature, including human nature, beyond any knowable limits. This optimism has been met throughout history with a chilling pessimism, which regards technology as a threat to humanity, the cause of social collapse, or the cause of the disenchantment of the world.

To understand our present moment, we need to trace this story from its beginnings. By examining how we got here, we can:

Understand the roots of our technological optimism

See paths we might have overlooked

Question assumptions we've stopped noticing

Most importantly, we need to step outside technology's frame and ask fresh questions. Like children encountering something for the first time, we must look at technology with new eyes—seeing it not as the water we swim in, but as a force that shapes our lives in ways we're only beginning to understand.

What Questions Guide Us?

As we embark on this search, we are motivated by the following questions:

What were the aims of the modern technological project? How does AI fulfill or cause us to revisit those aims?

What elements of our humanity can technology enhance? What elements do we risk losing?

How has technology historically changed how people live, work, and form bonds? How will it do so in the future?

How should we conceive of human reason’s role and limitations in guiding technology? What principles and ends should guide it? What constitutes genuine progress?

What new political possibilities and dangers will emerge, and how can we think about them in ways that are neither dystopian nor utopian?

To what extent should technological systems or principles govern human affairs, and how might they be limited in doing no more than they should?

Reading List: Recovering the Intellectual Origins of Technology (9 Sessions)

Session 1: The consequences of a world with self-guided machines

Aristotle, Politics Bk. 1 and Bk. 2.8

Every subordinate, moreover, is an instrument that wields many instruments, for if each of the instruments were able to perform its function on command or by anticipation, as they assert those of Daedalus did, or the tripods of Hephaestus (which the poet says “of their own accord came to the gods’ gathering”), so that shuttles would weave themselves and picks play the lyre, master craftsmen would no longer have a need for subordinates…

Session 2: The rule of the philosopher-scientist

Leo Strauss, “Liberal Education and Responsibility”; “What is Political Philosophy?” (pp. 36-40)

Philosophy or science was no longer an end in itself, but in the service of human power, of a power to be used for making human life longer, healthier, and more abundant. The economy of scarcity, which is the tacit presupposition of all earlier social thought, was to be replaced by an economy of plenty. The radical distinction between science and manual labor was to be replaced by the smooth co-operation of the scientist and the engineer. According to the original conception, the men in control of this stupendous enterprise were the philosopher-scientists. Everything was to be done by them for the people, but, as it were, nothing by the people. For the people were, to begin with, rather distrustful of the new gifts from the new sort of sorcerers, for they remembered the commandment, "Thou shalt not suffer a sorcerer to live." In order to become the willing recipients of the new gifts, the people had to be enlightened. This enlightenment is the core of the new education.

Session 3: The turn from utopias to the effectual truth

Machiavelli, The Prince, chs. 14-16, 25

But since my intent is to write something useful to whoever understands it, it has appeared to me more fitting to go directly to the effectual truth of the thing than to the imagination of it.

Session 4: Reforming the morality of men to prepare the conquering of fortune

Machiavelli, Discourses on Livy, 1.6, 2.preface, 2.1, 2.2, 2.29, 2.30

Thinking then whence it can arise that in those ancient times peoples were more lovers of freedom than in these, I believe it arises from the same cause that makes men less strong now, which I believe is the difference between our education and the ancient, founded on the difference between our religion and the ancient. For our religion, having shown the truth and the true way, makes us esteem less the honor of the world, whereas the Gentiles, esteeming it very much and having placed the highest good in it, were more ferocious in their actions.

Session 5: Human ingenuity as the production of imitations

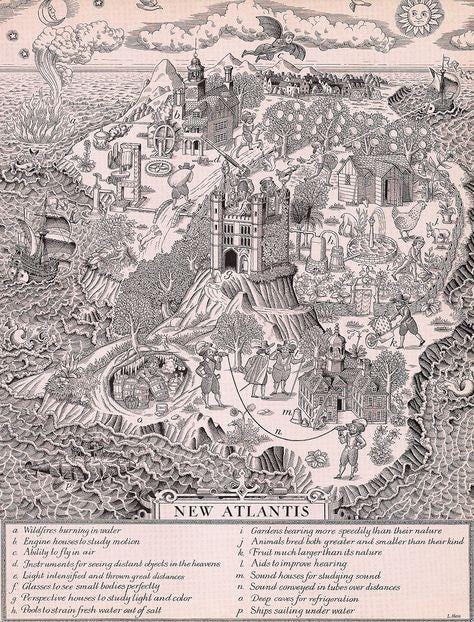

Bacon, New Atlantis

We imitate also motions of living creatures, by images of men, beasts, birds, fishes, and serpents. We have also a great number of other various motions, strange for equality, fineness, and subtilty.

Session 6: The new science as the mastery of nature

Bacon, Great Instauration

For the end which this science of mine proposes is the invention not of arguments but of arts; not of things in accordance with principles, but of principles themselves; not of probable reasons, but of designations and directions for works. And as the intention is different, so accordingly is the effect; the effect of the one being to overcome an opponent in argument, of the other to command nature in action.

Session 7: The liberation of man as his degradation

Tocqueville, Democracy in America, Introduction, 2.1.1, 2.1.2, 2.1.10; 2.2.1, 2.2.2, 2.2.5, 2.2.10, 2.2.20; 2.4.6, 2.4.7, 2.4.8

Above these an immense tutelary power is elevated, which alone takes charge of assuring their enjoyments and watching over their fate. It is absolute, detailed, regular, far-seeing, and mild. It would resemble paternal power if, like that, it had for its object to prepare men for manhood; but on the contrary, it seeks only to keep them fixed irrevocably in childhood; it likes citizens to enjoy themselves provided that they think only of enjoying themselves. It willingly works for their happiness; but it wants to be the unique agent and sole arbiter of that; it provides for their security, foresees and secures their needs, facilitates their pleasures, conducts their principal affairs, directs their industry, regulates their estates, divides their inheritances; can it not take away from them entirely the trouble of thinking and the pain of living?

Session 8: Nature’s conquest of man

C.S. Lewis, The Abolition of Man

Man’s conquest of Nature turns out, in the moment of its consummation, to be Nature’s conquest of Man. Every victory we seemed to win has led us, step by step, to this conclusion. All Nature’s apparent reverses have been but tactical withdrawals. We thought we were beating her back when she was luring us on. What looked to us like hands held up in surrender was really the opening of arms to enfold us for ever.

Session 9: Essence of technology as defining our “lifeworld”

Heidegger, The Question Concerning Technology

Likewise, the essence of technology is by no means anything technological. Thus we shall never experience our relationship to the essence of technology so long as we merely conceive and push forward the technological, put up with it, or evade it. Everywhere we remain unfree and chained to technology, whether we passionately affirm or deny it. But we are delivered over to it in the worst possible way when we regard it as something neutral; for this conception of it, to which today we particularly like to do homage, makes us utterly blind to the essence of technology.

If you’re interested in hosting a version of this reading group in your area, please reach out and let us know!

Perhaps a moot point to the august personages of the Cosmos Institute, but, for the sake of working stiffs like me, on what days and times, and in which places, is this thing happening?

Love this. 🤝. Love your work. We desperately need a new conversation about the history and philosophy of Science and #scientia - the canon of ideas & disciplines underpinning the scientific method - and it’s role in shaping modern humanity & its relationship with the values of the Enlightenment it helped drive. This is partly what I was driving at in my recent post:

...https://open.substack.com/pub/georgefreemanmp?r=6isp8&utm_medium=ios