For Aristotle, being realistic about the promise of AI requires us first to see what’s at stake

First installment of a new series from the Cosmos Institute’s reading group

Today’s AI revolution promises to be at least as radical as its industrial antecedent, which means that it won’t be possible to fully foresee, let alone comprehend, all of what is to come. But history teaches us that the best way to stand toward the unknown is to prepare to seize its possibilities. Are we clear about how we want technology to work for us? Do we see a clear path to improving life, society, and individual and cultural flourishing?

Earlier this month, Cosmos launched a reading group and response series on the intellectual origins of technology. Cosmos wants to prepare individuals to see the good that lies ahead. We believe that by understanding how the modern scientific and technological world came into being, we will better appreciate what modernity affords us, the trade-offs and compromises made in its development, and the unplanned surprises that emerged along the way.

The series begins with Aristotle, who clarifies the ancient view of technology and its proper relation to society. Starting with Aristotle and classical thought helps us examine the modern response, as represented by Machiavelli and Bacon. Both authors are historical pivot points whose projects of conquest–of fortune and nature, respectively–set the table for what we understand as modern life. Both self-consciously reject the received authority of the classical alternative, and we need to see why.

After examining the political and technological aspects of the modern scientific enterprise, we finally turn to three outspoken critics: Alexis de Tocqueville, C.S. Lewis, and Martin Heidegger. They all believe that technology poses particular dangers to the full realization of our humanity, though they understand those dangers in different ways.

Aristotle’s Approach to Technology

As the first session on The Politics showed us, it isn’t obvious how Aristotle will help us with our technological concerns. The text often seems historically distant, not infrequently offensive, and structured around sliding appeals to “nature” that pull between description, analysis, and moral judgment.

These reactions, however, are healthy and helpful. They pick up on the exotic character of Aristotle’s point of departure, which sets into relief our own deepest and often unchallenged assumptions. Since a big part of our purpose is to clarify our thinking, and to see what is unique and extraordinary about our own time, Aristotle’s difference–his strangeness–makes him a valuable interlocutor and teacher.

Turning to the text (Politics 1 and 2.8), we see that, though Aristotle’s main theme is explicitly political, there are six key moments where the theme of technology surfaces in important ways:

The delicate balance between tradition and innovation. In 2.8, Aristotle critiques the proposals of one Hippodamus, the first “philosophic” social scientist, rationalist reformer, and urban planner. Hippodamus wants to make correcting deficiencies in the law easier and use rewards to incentivize innovation. Aristotle, though he grants the soundness of Hippodamus’ reasons for wanting to innovate, critiques him on the ground that he misunderstands the nature of law and thus threatens to undermine its utility. Here, in siding with traditional and stable, if questionable, laws and habits, Aristotle indicates that the city’s stability does not rest on spontaneous unity alone. But if the city stands on a compromise between tradition and innovation, in what sense is its unity “natural”? And further, is there a standard for assessing how these elements can be combined in some optimal form?

The effects of self-guided machines. In 1.4, Aristotle broaches the question of “natural” slavery, setting a standard for the natural slave that seems to disqualify most extant forms of slavery (thus rendering them unjust). Intriguingly, he also pictures the existence of “self-guided machines” and even contemplates a world in which their existence would seem to make slavery mostly irrelevant. Despite this, Aristotle stops short of outright condemnation of slavery or advocating for its replacement with technology on moral grounds. Why is that?

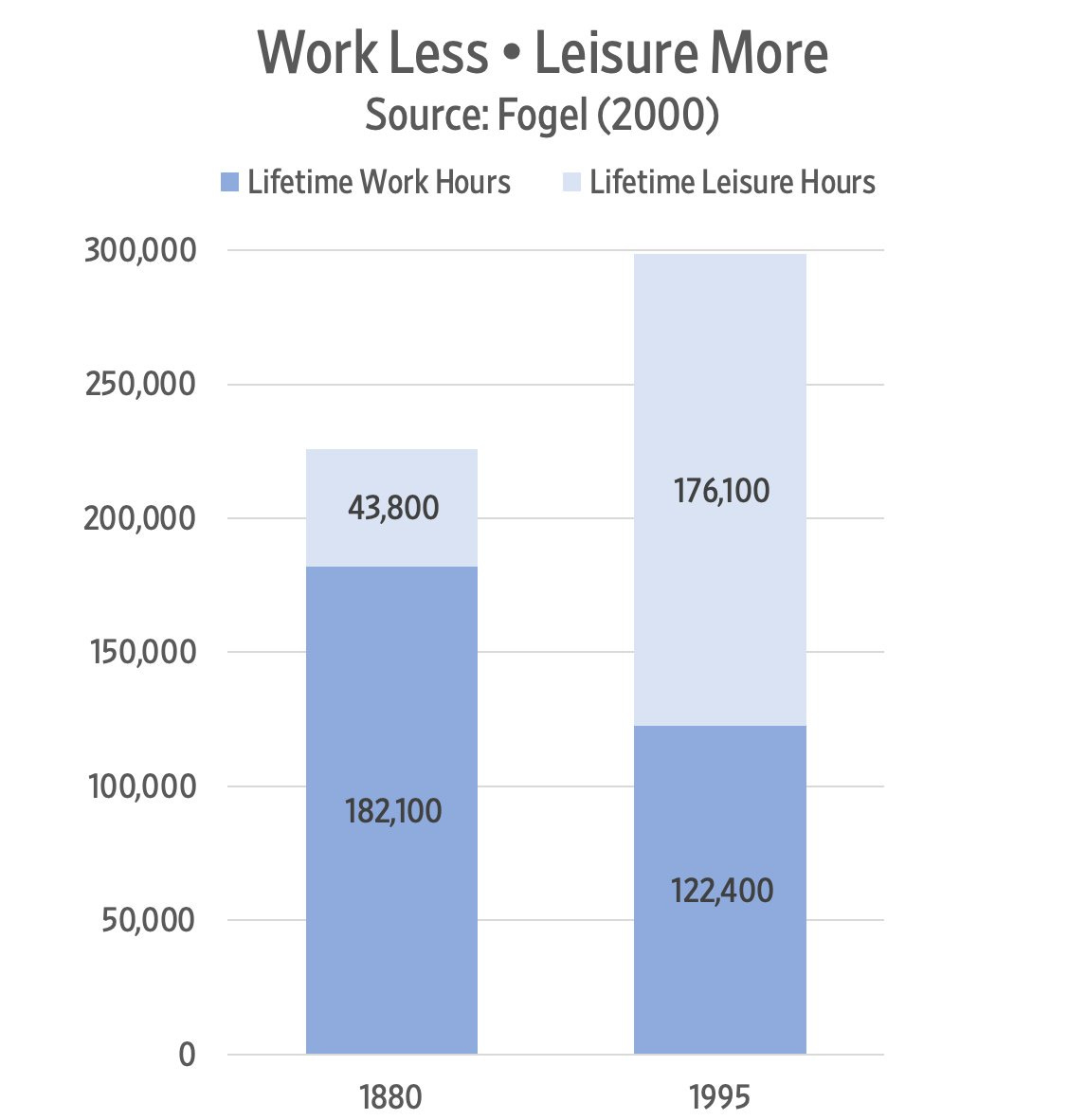

Hephaestus, god of craftsmen, whose tripods are described as having “entered the assembly of the gods of their own accord” Here, we can’t help but feel the shock of Aristotle’s position; abolition, including technology’s role in the outmoding of slavery, is a strong moral argument for modernity. Aristotle’s reluctance prompts a deeper inquiry: does technology truly offer a solution to the dilemmas surrounding labor and freedom, or does it merely shift the parameters of these issues? Further, does not the advent of technology accompany the need for immense societies with vast resources? While more leisure hours are available to us on average, what are the effects of this kind of society on participation in civic life or on the use of freedom? Has technology liberated humanity, or has it led us into a new form of existence–neither enslaved nor fully free, caught in a state of diminished citizenship?

The “naturalness” of the city and technological progress. In 1.2, Aristotle makes the case that humans are “teleologically” suited to living in cities, which means there is somehow a “natural” fit or complement between the city and our nature. However, Aristotle also argues that the city depends on a certain level of economic growth and technological division of labor. And given what he says later about economy and acquisition, it isn’t clear that any city of any size or scope is the city he has in mind. Even though this chapter seems normative or prescriptive, it turns out that the city’s dependence on technology may be a clue that the city’s putative naturalness is more in question for Aristotle than he makes it seem.

“Virtuous” acquisition and the absent role of markets. In 1.8-11, Aristotle discusses “necessary” versus “unnecessary” acquisition, where he condemns profit-seeking enterprises. Of course, there needs to be some level of economic activity, because the good life requires a certain amount of wealth. However, he stresses that commercial enterprises should not absorb the leading citizens because this would divert them from exercising non-instrumental virtues. Aristotle’s political economy causes him to downgrade the activity of mutually beneficial exchange. Yet, he indicates cities should know how to corner markets and create monopolies to generate the equipment necessary for a “virtuous” city. Here, again, Aristotle seems to concede that the city’s dependence on technology and related economic growth calls into question its naturalness. How can we understand the dependence on money-making and other practices like usury to support the leisure necessary for the good life? Why does he miss the role markets might play to liberate individuals to discover, share, and use knowledge to benefit the commons?

Infinite acquisition and the good life. Is wealth having greater quantities of material necessities, or having the instruments necessary to live a good life? And why do we desire unlimited money? One cause is that we fear privation and desire life without limit. This supplies us with a future orientation that makes us anxious to protect our continued prosperity. Because we are cast into nature with terrible scarcity and are naturally weak against the elements and competitors, we become risk-averse and desperate to acquire defenses for what we possess. The corollary is our desire for the increase of money, which we desire without limit to secure ourselves long into the future. The other cause is that even those who aim at living well mistakenly understand this to mean the gratification of bodily desires, which can be infinitely pursued.

Philosophy as a lucrative enterprise via technology. If we had any doubt that Aristotle was aware of alternative paths in political economy, his discussion of Thales in 1.11 at least makes it plausible that Aristotle understood the value of monopolies and how technologies can be used to generate new possibilities for market exploitation. Or put differently, Thales shows us that philosophers could use their minds to become wealthy but choose not to, and Aristotle seems to want his city–or his best version of the city–to reflect Thales’ hierarchical subordination of wealth or practical value to an end chosen for its own sake, in this case, contemplation, but in the case of the city, something like moral virtue or public deliberation.

We can tie these moments together by seeing them in light of the theme of the city’s naturalness. Whatever Aristotle might mean by the naturalness of political life, these passages make it clear that he cannot mean that the city is an organic or self-stabilizing whole. A city is not like a tree or a planet. Any political community is built up from parts or relations–like political factions, classes, or the relations between citizen and ruler, or husband, wife, and kids. The fact that Aristotle needs to clarify the parts of the city and, in so doing, indicates that they are often disharmonious or even at war is itself evidence that the city’s parts are not spontaneously in harmony or balance.

Why is this point about “parts” important? Because it shows us that a city needs to be governed in a specific way to hold together and provide good things. In the discussion with Hippodamus, Aristotle rejects the notion that a city can be subjected to a program of rational reform and progressive innovation. He believes that such a plan threatens the authority of law and tradition. What holds the city’s parts together is more rooted in habit and attachment than in rational calculation or utility maximization. And any effort to improve the city’s governance must acknowledge these sub-rational elements.

Aristotle’s response to Hippodamus shows us, in other words, that whatever is natural about the city does not produce a rationally distributed common good. The parts of a city are in balance, to the extent that they are, because of a lived history of trade-offs and compromises between the parts. If a city wants to grow its economy or innovate, it has to consider this history and how its stability might be affected.

The response to Hippodamus also helps us to see why Aristotle would attempt to set a limit on acquisition. Even though Aristotle grants that cities need to understand and deploy “unnatural” forms of gain, like usury, they ought to do so while upholding some sort of standard that subordinates wealth to higher, non-instrumental goods, like the well-being of the household and the moral virtue of the citizen.

Ideally, all parts of the city would share some conception of this limit, which would help the community persist as a whole. Given that this is difficult to achieve and that the parts of a city are likely to have competing views of distributive justice, Aristotle counsels rulers to educate the citizens to a shared sense of limit. This would be a prudential corrective informed by the need for stability–and would be all the more important if a city plans to grow its economy or trade sector.

Aristotle's argument compels us to acknowledge that if we believe our political community is not an organic whole, such as a beehive, and instead depends on tradition and respect for the rule of law (as stated in Federalist No. 49), then we must accept that growth and innovation are only possible within a stable constitutional framework. Yet, how do we know we have the right balance of dynamism and order? How do we know that our beliefs about progress aren’t just a “teleological” dream?

It turns out that Hippodamus, not Aristotle, is the wishful idealist. Drawn on by the allure of rational improvements, Hippodamus can’t help but assume that untried solutions will produce new forms of prosperity and integration. However, he has nothing like proof to stand on, and he completely fails to reckon with the actual realities of the city. Aristotle’s realism, by contrast, reminds us that unless we are maximally clear about what stabilizes our politics, any pursuit of innovation, especially new and powerful technologies like AI, should be treated with appropriate caution. Not because these technologies are intrinsically dangerous (though they might be) but because their usefulness depends upon their aiding, or at least not harming, the essential stability we need to flourish.

Aristotle helps us see that innovation and progress, properly understood, require a sensitivity to their broader effects on the stability necessary to moderate and rational politics. Our modern age pushes us to view the market exploitation of innovation as liberated from broader philosophical concerns. Aristotle helps us see that no innovation should be treated in isolation, and that the fundamental stability we take for granted requires as much attention as the innovation we so rightfully cherish.