Should we be optimistic or pessimistic about our AI future? What is intelligence in the age of AI, anyway? And how will AI impact human autonomy, independence, and excellence?

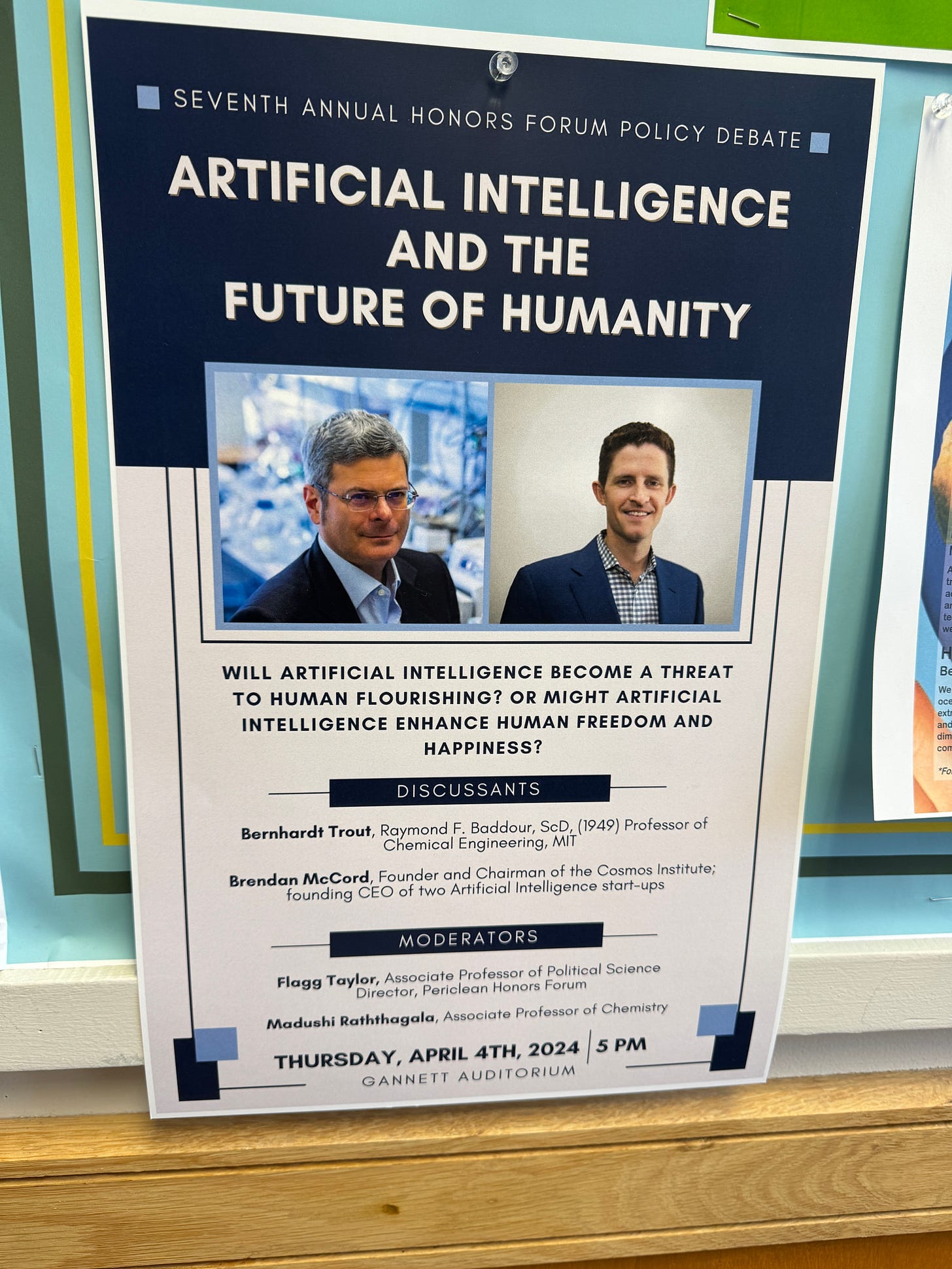

This spring, Brendan McCord and Bernhardt Trout met for a slugfest over these questions and more. Hosted by the Skidmore College Periclean Honors Forum, they both delivered opening remarks, then, prompted by moderator and student Q&A, went toe-to-toe on liberty and equality, virtue and freedom, intelligence and dogma.

Brendan McCord is Founder & Chair of the Cosmos Institute, founder of two AI startups acquired for $400M, and founder of the first DoD applied AI organization.

Bernhardt Trout is Raymond F. Baddour, ScD, (1949) Professor of Chemical Engineering at MIT, where he is the principal investigator at the molecular engineering laboratory and regularly teaches a course on ethics for engineers.

Below we publish Brendan’s and Bernhardt’s opening statements, their further exchange prompted by questions from the moderator, and audience Q&A (edited for publication).

Introduction (00:00 - 02:25)

Brendan McCord’s Opening Statement (02:25 - 17:00)

Different forms of intelligence

Philosophy of technology and progress

Inter-agent intelligence and catallaxy

The moral-political implications of AI complexity

Bernhardt Trout's Opening Statement (17:09-38:20)

AI, the decline of human freedom, and the erosion of intellectual virtue

The natural, the artificial, and the application of math to everything

What it means to be human

Distraction, work, family, friendship, education, centralization

Comments and Rejoinders: Brendan and Bernhardt (38:20-1:00:49)

Technological shifts and human adaptation

The problem of informational overload

Defining intelligence and abstraction

Emergence and complexity

Spontaneity, motion, and artifacts in Aristotle’s Metaphysics

Reductionism and AI

Moderator and Audience Q&A (1:00:49-1:22:47)

Positive use cases

The risk of homogenization and flattening of humanity

AI and moral agency

Nature of intelligence and consciousness

Centralization and control

Education and AI

Job displacement and the role of government and market adaptation

AI, Collective Intelligence, and Human Freedom and Excellence

Brendan McCord

Founder & Chair, Cosmos Institute

Introduction

The current AI paradigm, exemplified by ChatGPT, is characterized by systems that are human imitative, trained using explicit semantic knowledge on the Internet, and designed for one-on-one interaction between a human and a machine. I will make the case that an excessive focus on the present paradigm constrains our thinking about the diverse range of intelligences that can be realized.

Let us suppose there is a Martian version of the Skidmore CS department, and they send their emissaries to Earth for inspiration on improving their computers. What do these red planet ‘thoroughbreds’ identify as intelligent on our planet?

Undoubtedly, the human mind and brain stand out as one bright example.

However, they’d also notice that all around them, humans who were unaware of one another and pursuing diverse individual goals, were somehow cooperating and co-adapting to uncover social equilibria. They’d witness individuals making decisions based on dispersed, local knowledge while unwittingly sharing that knowledge and stimulating the creation of valuable new knowledge. The Martians would observe that this system was highly adaptive and resilient, worked at small and large scale, and had been operating for centuries without software updates or centralized control.

Can anyone guess which system I’m describing? [A marketplace]1

We humans don’t normally think of the market order as a kind of “supermind,” but the Martians, unencumbered by anthropocentric thinking, undoubtedly would.

Imagine if future incarnations of AI were inspired not only by the human mind and brain, but also by this metaphor of “inter-agent intelligence”--the emergent intelligence arising from the interactions of networks of diverse agents. In such a future, we can be optimistic about AI’s potential to support the energetic exercise of human freedom and the independent pursuit of excellence.

In what follows, I will briefly explore the connection between various forms of intelligence and the epochs in the history of philosophy. Then, I will illustrate the contemporary existence of a “supermind” that is ripe for enhancement by AI, drawing upon two crucial concepts–the twin forces of the “republic of science” and “catallaxy.” Finally, I will apply the insights gleaned from these ideas to sketch a path to a beneficial AI future that fosters freedom and virtue.

Philosophy of Technology and Progress

So how did science and technology contribute to the liberation and development of intelligence, both individual and collective?

Briefly: Starting with Aristotle and the ancient view, humans were not by nature isolated beings; rather, they were political animals who joined other citizens in a polis, or small-scale city, to cultivate the faculties of speech and reason to a high degree. This allowed for the full flowering of moral concerns for justice and the good life.

Although this perspective made the collective primary in a sense, the collective did not extend to science or intelligence. Instead, the philosopher conceived of his activity as culminating in the joy of isolated and singular contemplation of eternal wisdom--and even if this occurred in small schools like the Lyceum, science was far from a systematic, multi-generational, collaborative project to transform society or nature.

The moderns, however, thought they could outdo Aristotle--by making the world freer, more just, and more comfortable--through a new kind of civilization-scale project. Instead of admitting natural limits, 17th-century thinker Francis Bacon reoriented science into a limitless and open-ended collective endeavor to liberate the intellect and unleash human greatness from the constraints imposed by scarcity and birth. Teams of elite scientists began to carve out insulated and protected spaces that would harness the technology of the printing press to disseminate and compound the knowledge of their discoveries.

What took this development from merely a new vision for science to a model for world transformation was the emergence of Lockean-Smithian political economy by the 19th century. This school of thought defended and spread the collective intelligence of the market and what one might call “the creative powers of a free civilization.” This gave rise to grand technological inventions and human progress on myriad fronts, while uncovering and liberating a form of intelligence that we now recognize was severely suppressed in the ancient world: inter-agent intelligence.

In a moment, we will explore this concept as a novel frontier for AI and discuss how it can protect and promote freedom and virtue. But first, I will explain more adequately the existence of the most advanced form of collective intelligence known to us today.

Spontaneous Order as Metaphor

The modern project paved the way for the emergence of complex adaptive systems that far outstrip yet elegantly complement the scope of individual human intelligence. These new orders were “spontaneous,” or, as 18th-century philosopher Adam Ferguson put it, “the products of human action but not human design.” They relied on what we might call spontaneous and collective forms of intelligence, which two 20th-century thinkers, Michael Polanyi and Friedrich Hayek, made central to their work.

Polanyi shed light on the “Republic of Science,” formed by the indirect coordination of a community of scientists who adjust their work based on the results achieved by the others. He explains this by using the metaphor of solving a puzzle. Instead of working in isolation, each scientist attempts to solve the puzzle in view of the others, allowing everyone to benefit from each other’s adaptive attempts in a collective feedback loop. One cannot predict how the adjustments will be made, but the resulting progress is a joint achievement of unrestricted, unpremeditated, decentralized intelligence.

This mode of collective intelligence is mirrored in today’s market, which Friedrich Hayek called “catallaxy.” Catallaxy refers to the coming together of individuals with vastly different knowledge and purposes and the spontaneous self-adjustment of those plans via the price mechanism. Each individual unintentionally coordinates his or her actions with those of every other participant in the market order without any entity having designed or determined the resulting order from the outset.

The market isn’t the only complex intelligence that exists; but it’s distinctive from the ant colony or bee hive in that it benefits both the individual and the collective; as Adam Smith so elegantly put it, in markets, we obtain what we need by providing others what they want. Human self-interest is thereby diversified into collectively productive ends.

Whether in the production and distribution of food or the allocation of capital to new ventures, we could organize through communal consensus, global hierarchical socialism, direct democracy, or a state supercomputer. But these options would be inflexible, static, and inefficient. They’d stifle innovation and limit choice; make people dependent upon a centralized entity; and heighten the possibility of conflict over increasingly scarce resources.2

The “catallaxy” accomplishes these things efficiently without needing men to be angels or the existence of a superintelligent singleton. As economist Don Lavoie has written, “Minds, whether human or not, achieve a greater social intelligence when they are coordinated through the market than is possible if all economic activity had to confine itself to what a single supercomputer could hierarchically organize.”

AI and Complexity

Now how does all of this apply to AI? I’d like to suggest that Polanyi’s Republic of Science and Hayek’s notion of catallaxy illuminate the kind of intelligence that our interactions with AI could generate. Just as we do not fully comprehend the inner workings of markets, nor can we predict the innovations that will emerge from them, we do not fully understand how AIs will capitalize on inter-agent intelligence. But how might this work, concretely?

We foresee a planetary-scale web of computation, data, and physical entities, operating through market principles to make human environments more supportive, invigorating, and safe. In the words of Michael Jordan (the computer scientist, not the Space Jam actor) the inter-agent intelligence task can be thought of not merely as providing a service, but as creating intelligent markets that introduce new producers and consumers while breaking down information asymmetries to better align the needs of actors on both sides. And “actors” in this context can refer to both human and AI participants.

Two examples: In the case of goods and services–we’ve gone from static catalogs to AI-based recommendation systems. But in many domains, our preferences are so contextual, fine-grained, and in-the-moment that there’s no way companies could collect enough data to know what we really want. And doing so would require prying deeply into our private thoughts. Empowering producers and consumers via intelligent markets is an appealing alternative.

Another example is a revolutionary medical system that establishes a marketplace of data and analysis flows between doctors and devices, incorporating information from “producer” actors such as cells in the body, DNA, blood tests, environment, population genetics, and the vast scientific literature on drugs and treatment. This system would operate not on a single patient and a doctor, but on the relationships among all humans, allowing the knowledge gained to be applied in the care of other humans.

In both examples, the technical work is significant; it will require overcoming challenges like managing distributed repositories of knowledge that are rapidly changing and globally incoherent; addressing difficulties of sharing data across administrative and competitive boundaries; and bringing economic ideas such as incentives and pricing into the statistical and computational infrastructures that link humans to each other, to AI actors, and to valued goods.

According to Michael I. Jordan, domains such as music, literature, journalism, and many others are crying out for the introduction of such markets, where data analysis links producers and consumers.3 This vision can be realized only if we broaden our conception of AI from chatbots or Go champions to tools that stimulate new forms of inter-agent intelligence.

The Moral-Political Implications of AI Complexity

I’ll close by framing the moral-political implications of this vision for humanity’s AI future.

While philosophers of old believed that a virtuous order required a hierarchy of purpose embodied in and enforced by law or regulation, this is not how the marvels of the modern age have been achieved.

Instead, a commitment to the abstract ideas of the rule of law and natural rights has liberated individuals from coercion, privation, and drudgery, giving birth to a decentralized, spontaneous order: an inter-agent intelligence that in turn brought about modern medicine, improved transportation and housing, yielded widespread material abundance, opened near unlimited access to creative works, and enabled tremendous growth in leisure.

If we shift to a new model of AI design that supplements and enhances this collective intelligence rather than subverting the individual, AI will extend our liberation in unpredictable but directionally positive ways. Freedom and virtue are possible–but not assured. We must be awake to the dangers that lurk in the more banal possibilities for the future, and in this I think Bernhardt will agree.

In Democracy in America, Alexis de Tocqueville warned of a “soft” despotism–the idea that we might welcome a centralized state because it promises to relieve us of “the burden of living and the pain of thinking.” But, bit by bit, this renders us dependent on it–ultimately limiting our energetic use of freedom and undermining the greatness we can achieve.

To counter this subtle threat, Tocqueville advocates for strengthening the individual to protect their autonomy against impersonal forces of all kinds, be they majority opinion or algorithms. Virtue, in this account, requires the independent and free use of high human capacities that would otherwise atrophy. It also requires liberal education to fortify independent judgment so we do not give up thinking.

This is the task of AI development in the next era: creating more tools that supercharge the spirit of individual independence in the spontaneous order, that generous realm of freedom that is the chief facilitator of energetic striving after human excellence. Just as using markets in the service of human flourishing takes dedicated work by all of us, using AI for human flourishing will be similarly demanding. On this view, we are not looking at an escape from human agency: an AI supermind neither provides automated damnation nor automated salvation.

At stake is not merely individual greatness but the greatness of our civilization as a whole. Hayek, like Mill before him, reminds us that the dynamic power of a free civilization depends upon the vigorous coordination and clash of a great diversity of thoughts and actions. Without that diversity, civilization would be reduced to mediocrity.

I’ll end by paraphrasing Tocqueville. We will not be able to choose whether or not we have AI; halting development, like halting democracy, would be as impossible as it would be unwise. However, it is up to us whether AI will lead humanity to servitude or freedom, enlightenment or barbarism, prosperity or misery. In China, we witness one possible future, where the motives of safety and social control render citizens dependent upon a centralized, AI-enabled despotism. Leveraging the energy and efficiency supplied by AI's catallactic possibilities through inter-agent intelligence presents a powerful antidote to dependency and intellectual enervation in our times.

Artificial Intelligence and Humanity

Bernhardt Trout

Raymond F. Baddour, ScD, (1949) Professor of Chemical Engineering, MIT

Many thanks to Professor Taylor for the invitation to discuss this most important topic and to Mr. McCord for joining the discussion and for his important and helpful starting speech. Also, more broadly for his interest in liberal education and applying it to address the challenges that society faces with the rising dominance of AI through his Cosmos Institute. I have also benefited immensely by discussions with Mr. Stuart Diamond, Dr. Steven Lenzner, and Prof. Svetozar Minkov.

The question under consideration is whether AI might become a threat to human flourishing or might enhance human freedom and happiness.

Brendan McCord argues for the latter, and I for the former.

Let me start out by saying that I do not doubt that AI has the potential to enhance human freedom and happiness. I myself am applying AI for drug development, as are many others. Health is certainly an important aspect of freedom and happiness. Autonomous vehicles will give us the potential to make better use of our time. AI-enabled innovations will transform retail sales, allowing us to obtain more goods that we want more quickly. In general, AI will create more abundance, giving us all more “equipment” to use Aristotle’s term. I note, however, that equipment is only the most basic need for human beings. It is not the end of human beings, which must be something higher than mere bodily function or enjoyment.

At the outset, while keeping in mind that AI is a potential “existential” threat that could destroy us by going haywire or alternatively annihilate us via AI-enabled warfare, I would like to focus on what AI does to us when it works as intended.

My concern can be stated succinctly: As we allow AI to do more and more for us, we will be giving up our freedoms and concurrently the ability to use our minds. In a word, we will give up that which makes us human.

I first want to draw your attention to the fact that AI is already diminishing us. For example, Jonathan Haidt, a psychologist and social media researcher has compiled a vast amount of data from a wide variety of studies and found some terrible, although not surprising results. Mental illness among teens that is correlated with the rise of social media (AI-enabled) has increased tremendously, between 50 and 150%, depending on the indication. This is devastating and affects girls more than boys. It cannot bode well for the future.

Another disturbing fact relates to how we spend our time in a world of AI-enabled devices. According to recent research summarized in a 2023 article in Fortune Magazine, Americans spent 4.5 hrs/day on their smartphones, a 30 percent increase from the previous year, and we checked our phones an average of 144 times per day. Does anyone think that such distraction doesn’t hinder us in pursuing what should be our goal: becoming better human beings? Does anyone think that with the continued rise of AI, such interaction with electronics will not increase more and more as people engage less and less in the world, the real world, the non-digital world, and perhaps, in the end, be so plugged-in that they have forgotten it? For the digital world is the world of distraction, and it fulfills oh so well the modern desire for constant and immediate gratification.

Distraction may be pleasant or may allow us to forget our pains, but it does not give us those calm and quiet periods that are needed for cultivating ourselves, whether it is learning music, art, mathematics, or science, or most importantly, understanding ourselves.

I will go more into those human subjects shortly, but let me start out with what AI is and is not. First of all, by its very name, it is artificial. It is a product of artifice as opposed to nature. It is constructed by human beings, but it is not even artificial in a way that objects are like a pot or a table or even a computer. That is because it is a mathematical abstraction. It is not a thing. It is a mathematical formula, a highly complex, non-linear formula, but nothing more than a mathematical formula. And mathematical formulas can never capture fully anything artificial, let alone anything natural. Let’s start out with the pot. Perhaps mathematics can capture its shape reasonably well—mathematics is particularly suited to shape. But how about its color? The application of mathematics to color turns it into wavelengths. I don’t know about you, but a 474 nm wavelength does not seem to me to be an adequate representation of blue. Going further, what about the significance of an image on the pot, perhaps Odysseus tied on the mast of his ship, listening to the sirens’ song? Turning that image into numbers changes it even more than turning blue into 474 nm.

And that is a simple pot. How about natural things? We have a joke in chemical engineering that illustrates the point. The joke is that chemical engineers model a cow as a sphere. Well, no one is laughing, which indicates either that no one here is an engineer or that engineering jokes are not funny. At any rate, let’s say we model the shape of the cow better, much better, with an extremely fine resolution, say on a very small grid, far smaller than nanometers, and say we do that in 3D, somehow capturing the inner workings. It is still a model and still necessarily misses aspects of the cow, important aspects. In fact, our mathematical model of the cow is a particular abstraction made for some pre-determined purpose. For example, we might want to understand the efficiency of its metabolism, and we put in our model all of the metabolic processes. Thus, we have abstracted the metabolism from the cow. Or let’s say we want to do visual recognition. Then, we have abstracted the appearance from the cow. Any mathematical model is an abstraction that is severely incomplete, for it is a particular abstraction done for a particular purpose, chosen by a human.

But as bad as mathematics is as a description of inanimate objects or animals, the deficiency of mathematization is most poignant when it is applied to human things. Beauty, love, thinking, striving, and justice, to name a few, are not amenable to mathematization. Abstracting these human things into mathematical formulas transforms them so far from what they are as to make them unrecognizable. If Beatrice from the Divine Comedy were modeled as a mathematical formula, points on a grid or some large polynomial with addition terms added, we would be hard-pressed to understand that as beauty or charity, or even as a human being.

That brings me to my next point about AI, what it is not. It is not intelligence. It cannot define a purpose, but must be programmed by human beings who do possess intelligence and who intend a particular aim. Even if generative AI can produce its own models, it must be given commands by human beings, at least originally. AI cannot initiate.

We use terms like “learn,” “recognize”, even “hallucination” to describe AI, but these terms are merely anthropomorphizations of mathematical functions. AI does not appreciate pleasurable things (strawberries and cream, to use Turing’s example) or anything for that matter, since it cannot appreciate. Even more importantly, AI does not have moral capacity--it is after all only an algorithm in a massive calculator. Whatever results come out of an AI algorithm that we humans think of as moral decisions are not decisions at all, but the outcome of programming, based on a utilitarian formula inputted by some programmer whom the rest of us might not agree with; whom we probably don’t agree with. We probably don’t even agree with the whole moral framework behind the programming. Even if we do agree with the programmer, the programmer could not anticipate every situation or any specific situation for that matter. The algorithm will minimize the difference between its programmed model and its mathematical abstraction of a specific situation, resulting in an outcome. There is no moral agency.

Before I move on to humans, I want to raise another limitation with the application of mathematics to describe nature, a tremendous limitation. Above and beyond the impossibility of a model to capture everything about an actual object, it cannot treat what governs perhaps half of the world. It cannot treat chance or, if you wish, randomness. It cannot generate random numbers and can only treat the randomness of events in the aggregate, in the limit of a large number of the same type of event. Yet, randomness is taken to be intrinsic to physical processes, such as the motion of an electron or fluid flow. It is even taken to be intrinsic to economics and politics. Everything that we do involves chance at least to some degree, every choice we make, every interaction that we have with our fellow human beings.

In sum, any AI model is necessarily incomplete, a mathematical abstraction from the world to shape, an abstraction for a pre-defined purpose chosen by the programmers. Its intrinsic limitations are the intrinsic limitations of mathematics, including its inability to treat chance.

Now let me move to discuss what it means to be human. This is clearly an even bigger topic than the artificial, and time is short. So, I will focus on a few themes that I hope you will find compelling. Being human means cultivating oneself towards some aim. But not just any aim, a worthy aim. To reference Aristotle again, the higher aims are those activities that are ends in themselves, like art, science, sports, or serving one’s country or religion. Friendship is another end in itself.

An AI bot cannot pursue ends for their own sake, because it is purely utilitarian. At best, one can say that for AI, there are only ends. But could AI help us in our pursuit of higher aims? Certainly it could, by compiling information in a useful way, by allowing us to be heathier and by giving us more time for worthwhile activities. It will certainly increase the progress of science. For as a product of science, it is particularly suitable for that.

But to say that it could doesn’t mean it will, and in fact, I think the opposite will likely result. AI is made to address the quintessentially modern desire for immediate and constant fulfillment without actually leading to fulfillment. As such, it is in particular good at distraction. Extra time that AI might give us will most likely be spent on mindless entertainment or surfing the web, or on drugs--according to Gallup 17% of people in the US use marijuana regularly. Given the incentives of those running AI companies to increase usage as much as possible, it is hard to see people becoming less distracted with an increasing prevalence of AI. Moreover, technological society itself creates the perceived need for distraction as a way of addressing alienation or miscontent with the utopian expectations promised but not delivered by technology.

Pursuing those activities which are ends in themselves, what makes us better humans, include work, friends and family. Family and friends are on the decline, and AI is set to transform work, unlikely for the better. Will AI provide an adequate substitute for those or address the mental health crisis that it caused? That also seems unlikely. The problems that it causes seem to be intrinsic to its operation.

AI might not have started all of these declines, but it is certainly contributing to them if not increasing their acceleration.

The best remedy, the only remedy that I know of that could really address these issues is education, a particular kind of education. That is a liberal education, in which students study the most thoughtful writings to learn about the world and themselves, an education in which they cultivate their minds to become worthy of the term liberal, free. In elementary and middle school, students can be prepared for such an education that can start in high school and begin in earnest at the university.

But how is that looking? Without basic skills, a liberal education cannot even be started. Yet, a recent Washington Post article (June 28, 2023) summarized some statistics: only 13 percent of eighth-graders met U.S. history proficiency standards, “the lowest rates ever recorded” and 31 percent were proficient in reading, 26 percent in math. Once students get to the university, even if they have the basic skills, they will find a desert of mediocre conformity with only a few rare oases. Hardly a teacher of liberal education is to be found these days.

Will AI address those issues? I don’t see how, particularly since AI is geared towards conformity. AI companies run by very smart people who have not had a liberal education, might attempt to address the statistics of decline via AI. But how might they do so? If generative AI can effectively do reading and math, why not just teach students how to use generative AI? That seems to be the most likely outcome. But generative AI produces output according the prejudices of its makers. As uniform as the thinking of our teachers is, imagine if the 4 million of them are replaced with a few bots.

Concurrent with the AI-generated centralization of education, there will be a continued increase in the power of the elite who wish to manage the rest of the country and will be able to do so with more and more powerful tools. The rest of us will continue to be more and more distracted, so we will learn less and less, even as we become more and more dependent on AI. That quiet and lonely time that is needed to better our minds will dissipate. The elite will use AI to promote whatever politics they deem right, but without the education to have thought through the issues or the consequences of what they do, they will absorb whatever is trendy and fix those trends into their algorithms. They will try to better the world with algorithms, using their unreflected upon views of better and imparting them to the rest of us. They will promote two poor qualities, moral indignation and a feeling of moral superiority.

Between constant distractions, lowering expectations, and indoctrination through AI, the young will grow up to be less and less self-sufficient and less able to know how to make good use of their time.

AI deals with the average or the mediocre. It is “trained” on huge amounts of data such that the resulting model fits the data the best. It doesn’t work well with little data and therefore doesn’t fit the rare or the high. The end trajectory is conformity among the masses and conformity of production of AI among the elite.

Am I saying that all of this is inevitable? Not at all. We could continue to increase the use of AI to run our key systems, like the energy grid and defense, to enhance medicine, and even to learn, while refusing to give up human intervention and decision-making. We can reform our schools and universities to focus on liberal education, and we can as a society promote freedom and thoughtfulness. If we do those things, AI can be used enhance human flourishing, but that will be despite AI, not because of it.

Comments and Rejoinders

Flagg Taylor [moderator] Brendan, do you have a response to what Bernhardt has put on the table?

McCORD: Yes, thank you. The question I have--and then I have more to say about intelligence, so I want to treat that in a little bit more depth--you started by talking about some of the proximate harms (Jonathan Haidt’s research has illuminated one example). A response to that is that humans have adjusted from a hunter-gatherer society to agriculture, and to urbanization. These very large, multispectral changes were, in their early stages, far from easy. Why isn't what's happening now another example of that, where we have difficulties in the near term, but the medium term benefits are enormous?

In the case of social media and Twitter, could the benefit be improvements in connecting and enhancing networks of very smart people with compounding effects and synergies, such that in areas where we can measure performance --apart from, say spelling, which you highlighted--we're doing a lot better than our ancestors in almost every realm? I think the benefit especially accrues to very smart kids in poor countries. So why is it not another example of that; something we have adapted to in our history?

TROUT: You mentioned the example of the printing press, which was a tremendous innovation. The difference before and after was that before the printing press, very few people had access to ideas and writing. It would be a very small number of people who were part of that elite. So the printing press was instrumental in allowing--sort of a democratization if you want to call it that--ideas to be propagated to others.

The difference now is not a lack of information; it's too much information, and there's so much information out there, we have to spend all our effort to sort it out. The best way I think to do that is by turning off the computer, turning off the smartphone. The solution is not in AI because by construction, it's created a problem that it itself cannot solve.

McCORD: The broader point that I wanted to make was the notion of what AI is or what it is not. And I'll paraphrase inadequately, but you said that AI can't define a purpose; it has to be programmed instead by human beings, it’s not intelligent, and it’s anthropomorphized.

On the last point, I agree with you. There’s an interesting paper that talks about the ways in which language attaches to concepts in a restraining sense, and the paper advocates that we should look to authors like Jorge Luis Borges, a magical realist who had no difficulties expanding the lexicon. Understanding weather patterns through the moves of the gods only goes so far; we use what's available to us, but that only goes so far--we have to transcend them. So I agree with that.

But on the point of purpose and intelligence: I don't have an adequate definition of intelligence, but it has something to do with the ability to form abstractions, give semantic interpretations of thought and to precepts. It's not only this, but I think that's part of it.

And you mentioned that AI is a particular kind of abstractor that is capable of generating highly refined abstractions. An example that I heard from Dario Amodei from Anthropic a few weeks ago: models, even in the current generation, are very good at adding 30-digit numbers. There isn't a lot of data on that in the training set; people don't do a lot of 30-digit number addition. What they believe is happening is that the circuitry inside the model seems to be implementing the addition algorithm. It's finding an underlying simple structure, a more parsimonious way to solve the problem such that it's developing another abstraction. So that's an example--kind of a toy example--of an abstraction that is capable of then finding its own alternative abstractions. This seems like a rudimentary kind of intelligence.

Intelligence seems to be an emergent, system-level property. You have described the cell; the neuron that has proteins, ions, interacting in complex ways that yields three-dimensional electrical and chemical activity. The properties of the human mind are the result of these complex interactions. The question is can AI have that kind of emergence?

You evoked the duality of our artifice versus nature in talking about what AI is. My test for whether something is emergent: can you compute the capabilities of the thing as the sum or as the average of the programmed elements? If you can, then it's not emergent; if you can analyze causal chains to determine the result and capabilities, it’s not emergent. But if the capabilities depend sensitively on certain characteristics given by original programming, and if the resulting order doesn't depend on specific causal chains, and if it's robust under local perturbation--you can take out various parts and you find that the intelligence or that the emergent property is not possessed in these parts--then it is emergent.

Going back to Aristotle, who is joyfully featured in a couple of remarks so far, he draws a distinction between natural substances which have an inner source of motion, intrinsic teleology, and artifacts which have a motion or purpose that is imposed extrinsically by the artisans’ technical expertise. He says that nature arises from innate principles versus human artifice arising from reasoned imposition, from the form of matter.

When I read the Metaphysics, he seems to allude to the possibility of a third way for things to come to be, alongside nature and craft. He seems to say that it can come to be from chance or luck, in quite a similar way to the way things come to be from nature, but without seed. It’s too much to go into all the textual support, and indeed it's scanty--he doesn't really flesh this out much--but he basically cracks open a door to a kind of artifact that transcends its metaphysical status as the product of an external craft and starts to exhibit its own inner principle of change just like a natural substance. So, it's an artifact that's composed of self-moving matter.

There’s an undeniable propensity of humans to prefer to deliberately create an arrangement to result in emergent behavior, but I do think the essence of AI systems--especially if we let ourselves imagine what they might be in the future--seems to lie as much within their dynamical becoming as in their original constitution. Yes, original programming comes from humans. But what has developed--the abstractions that result, the discovery of the addition algorithm or the purposes that get modified along the way (if the artifact is coded to be able do that kind of thing)--that seems to shift away from authorial intent such that the essence is actually separate.

TAYLOR: So I just want to pause to note that the future of AI may hinge on the proper interpretation of Aristotle’s Metaphysics. Run home and get the book out!

TROUT: When you talk about emergence, I'll make two points. So, I haven’t studied the Metaphysics for about 10 years, but I think by spontaneous, i.e., the third way, you mean with his use of the words apo tou automatou, which is just another phrase for chance essentially, in contrast with fortune. And I think that the reading is not that something can emerge spontaneously and that can become effectively a natural being with its own innate source of motion. I think it's just chance that things emerge in nature: a particular mountain emerges or a particular something that looks like what we have in New Hampshire near where I live—there was a rock formation which is called “The Old Man of the Mountain,” though unfortunately it fell down. But it looked like a man--that's all Aristotle means by emerging spontaneously.

I want to get to another point of yours, which is central to the issue. You mentioned neurons and then all the cells and the neurons, how they differentiate and come together, collect and form, and you find that somehow that's what thinking is. I don't agree with that. I think that there are natural wholes, like human beings or each one of us. You can reduce us, through a reductionist approach, to the neurons, the cells, but for that matter why not just the atoms or the electrons and the protons and neutrons?

These are particular kinds of abstractions--exactly the kind of models that I was talking about earlier. They may not be mathematical in the strictest sense, but they're very much related to these mathematical abstractions. So if you say that the human being is just the neurons and the other cells or maybe it's not just that because something emerges, then I agree that you’ve reduced the space between the AI algorithm and actual human beings as natural wholes. But you have not necessarily elevated AI to intelligence but instead reduced human beings to something that's actually not intelligence--something that's just material.

TAYLOR: Let me ask Bernhardt a question, and I'll ask you a similar one, Brendan. Can you think of a discrete use of AI that is actually working out well, which is, in some sense, beneficial to humanity, and does not introduce the problems that you discussed? Could that particular case explain how a future can be cultivated where we can actually use it positively?

TROUT: Sure. In terms of health, drug development. Interpreting medical results using anthropomorphic terms that reach conclusions. But yes, if we can use this and apply it to subjects to which it should be applied, AI is a product of science and it's applicable to science. It's very applicable to the progress of science with progressive fields. I think in terms of relying on it for human interactions, connecting people, it tends to be good but it seems to have the trend to lead to the unfavorable outcomes that I mentioned earlier.

TAYLOR: To you, Brendan, the counter question to you would be, is there a discrete example of AI that you're troubled by, that we need to manage better in order to go in the direction of the more positive scenario that you sketched rather than the negative one?

McCORD: I'll give two answers here. The first one is not one that I'm deeply troubled by, but I think is a key limitation of current systems. It has to do with the difference between knowledge creation and automating what we already know. For example, we do tumor detection in the case of cancer. This is helpful--I'm not against doing that! But it is possible, I believe, to use AI to expand what we know about cancer. And in my analogy here, I would say that the airplane and the electron microscope didn't automate flying or looking at subatomic particles; we just didn't do those things prior.

So the question is: do we need to limit the technology to automate what we already know, or are we capable of imbuing the technology with characteristics where it could do knowledge creation? My view is that today, we can't do the kind of reasoning that's necessary for scientific discovery, and that instead, AI does common sense reasoning in sort of a comprehensive generative repository of common sense judgments. I don't think it adds up to the kind of reasoning that's needed for either open-ended science or trustworthy assistants and tutors or robustly respecting moral constraints. So that's one.

The other is, in terms of what I think is problematic, I--like Bernhardt--am worried about the flattening of human life. I'm worried about a homogeneous viewpoint. This could be a consequence of having billions of human minds’ attention allocated by recommender systems that are geared towards ad clicks or dopamine response and they are made by just a few companies.

So with my argument, I tried to lay out a model in which the supermind wasn't a kind of singleton that was either trying to marshal all resources for paper clip production or trying to encode a kind of unitary social welfare function dominated by single objective.

It's a kind of supermind that has value pluralism built into the foundation, in a way, and that causes intellectual autonomy to be preserved and to grow. So I think that's a harmful one that I’d like to work on; we are standing up a “philosophy-to-code pipeline” to try to explore solutions to that or to try to experiment and learn more about that problem.

Madushi Raththagala [moderator] I listened to both of your opening remarks, which concerned how AI systems process information, learn, and take positions. But I feel that this isn't what you said. I feel that AI systems lack consciousness or self-awareness. So my question is, by using machine learning or neural networking, can you make AI systems conscious? If you can do that, isn't that a better way of regulating AI systems?

McCORD: I don’t have a deep enough understanding of what consciousness entails. It would be wise to create AI systems that could robustly respect moral considerations. Those are the kinds of systems that I would think I would want my four-year-old daughter to interact with--systems that are capable of doing that. Whether it’s salutary to classify AI systems as moral agents as a way of regulating--is an interesting question. I’m not sure I have a good answer to it.

RATHTHAGALA: You talked about AI bias, right? If you want to align the human for the use of AI for its own benefit, could you change the AI system to be more conscious? Is this the same as a regulatory system?

TROUT: If it's a model of humans, humans often are not self-regulatory. So, I think I made the case why I didn't talk about consciousness. If we are nothing but mathematical objects, let's say that basically you can describe mathematically, then I think consciousness could be modeled. So I think the best that will happen is that these AI bots will mimic self-awareness, mimic consciousness, and will proceed to adjust society according to how they’re programmed.

Even if something emerges that was unexpected far down the line--and I agree with you, you could find emergence as such, you can say the entities emerge--if that's the case, and, again, I'm not saying it is, I think there are strong reasons why this will not happen, but even if that is the case, what is going to happen? Companies are going to produce bots that look like human beings and act like human beings.

Let's just think of the best possible outcome: each of these bots is more impressive than any real human being. It seems to me what's going to happen is that each of us as individuals is going to end up spending all our time with these bots. Even if everything works perfectly, these bots are going to be amazing teachers, even better than the teachers you have here. They’re going to be amazing friends, even better than all your friends. They're going to be better than anyone. In that scenario, we won't go extinct necessarily because of the bots, but it's because we'll have no more need for human beings. We’ll spend all our time with the bots, we’ll disappear, and then the bots will be left with themselves.

McCORD: I'll add to that in agreement with Bernhardt. There’s an idea from Rousseau about amour-propre. It has to do with the self-recognition that we seek in others. And we don't seek this from our television sets or from our cars (most of us…) but we may, in the case of AI systems, experience that desire for recognition. Humans don't really know how to navigate a society like that. The response from my end is to acknowledge that this is a challenge that is novel in a world-historical sense, but also to say the only way through seems to be emphasis on liberal education or on the autonomy of the individual--giving the individual enough resources to be able to think through that and to have a foundational self that is resilient to the AI boyfriend or girlfriend.

I also think there are ways of developing artificial intelligence, this inter-agent model, that are less about replicating so that you have a boyfriend or girlfriend in a virtual sense and more about trying to cultivate better interactions and mutual adjustments among agents, be they AI or human.

Audience Q&A

Question 1: Is AI art “real” art?

My question is for both of you. It came up because I love art, and virtual and AI-created art has become increasingly popular. The question is, is AI-created art “real” art?

McCORD: This is interesting; an area that I want to think more about. I know Nietzsche has an aphorism in The Gay Science about what we owe to artists or what we should give to artists. This is something that Cosmos is studying in an upcoming class that I’m teaching at Oxford this spring. We’ll have a segment on creativity. But I can't say that I've thought about it much yet.

I probably don't have the purist’s definition of art. I don't think art has to be didactic. I don't think art has to be scarce. I buy lithographs sometimes. I don't always buy printed productions, but I'm ok with replication as art. I take an individualistic approach to what art is and maybe what that means is that I don't have an overarching purity test in mind. So I would tend to err on the side of yes, AI art is art.

All art trends--whether it's Warhol putting a Campbell soup can up or the kind of flatness and movement that Pollock exhibits--are movements that, on the one hand, disagree with what came before and, on the other hand, preserve a lot of essence. If you were a Martian, you would see some common thread of what that art is, even as they try to portray themselves as rebels. I think we'll experience this cool combination of a through line of what we consider to be art. We'll be able to look back and say that there was actually a thread with Pollock, with Warhol, with Michelangelo, but that it will be different, rebellious, and new.

I think there will be a lower single-to-noise ratio in the future for obvious marginal cost reasons, and market costs are tending much much lower, and so there may be a lot more junk. This could create power for the people who become the next Le Monde, that the “Right Bank” of Paris will be important because we may seek expertise to help us sift through it. That’s all I have thought about it.

TROUT: I would go back to the issue of simulation versus reality. I'd love to have a simulated audience where everyone laughs at my jokes all the time, but I'd rather have you actually as real people, and when you laugh, it's real rather than this amour-propre that Brendan mentioned, or a means to get this attention.

I think it's the same with art because here's what's missing in AI-generated art--and I'm excluding the possibility that AI-generated art is actually done by artists per se, versus programmers who somehow have some database created from that, so it's truly a product of the simulation. The difference is that art, or an artist, is a certain kind of life. This artist has made a decision and cultivated herself towards living a certain type of life, which leads to maybe a certain inner focus when the art is an external product of the inner focus. If it's done by a human being, it has that kind of reality.

That is one of these activities that (I mentioned from Aristotle) is an end in itself, so it's intrinsic. If it's a pure simulated art, all that is being removed, and I think it does have an effect. It doesn't mean we can't all be deceived and end up living our lives in deception, but that is exactly the kind of outcome that I was saying is not a good outcome.

Question 2: What is so unique about the harms of our AI moment?

I had a question specifically for Professor Trout. There are a couple of points that you made about the cons of AI and AI in our society, specifically about changing values. For example, it is already diminishing humans in terms of mental illness, for instance via social media and time wasted on devices, which enables the power of the elite. What I was thinking about throughout the examples that you brought up is that these systems that you mentioned and these degradations, these have happened all throughout history. The ancient Romans, when wax tablets were introduced instead of papyrus, there was outcry and they were saying this is a degradation of our writing system, why are you doing this?

The power of the elite has always been there throughout history. They controlled the mass in various ways: before they used the printing press, then they used nuanced social influences. I don't know if you can construct a society without pilots. So, what makes this kind of AI different from any other cataclysmic event in the flow of time? Are we just moving into a different flavor of what humanity looks like?

There are certain values that we hold dear and we're not comfortable with those values changing, and maybe we are now moving into a new era dominated by dopamine hits and clicks, etc. But, in 1,000 years that will change again and we'll have a different flavor of what humanity looks like. So--and I wouldn’t say this is necessarily a bad thing--but I’m interested in hearing your thoughts?

TROUT: If it can be used appropriately, it's not necessarily a bad thing--but the difference is that, according to Rousseau, technology leads to more and more amour-propre. But I would say that the difference here is that AI presumes to be all comprehensive as a technology. It's addressed every aspect and we've mentioned a few, certainly economics, health, politics, language, art. So it's all comprehensive--so that's the difference.

One of the best articles on this written is in the Atlantic by Henry Kissinger is called “How the Enlightenment Ends.” So here's this Enlightenment project releasing science and technology for the benefit of humankind, except that if it becomes all comprehensive, then it could lead to the end.

McCORD: If I can add to that, I would say that the risks that Bernhardt is raising are very rarely raised. Usually when we talk about risks of AI, we mean catastrophic risk, that AI is going to kill us all. This is a kind of dominant approach in the practitioner community to view the question of risk through a narrow utilitarian lens. The narrow utilitarian lens ignores deep subtleties of moral questions, including some things that are endemic to morality. It does so in part because it's very easy to map this way of thinking to optimization techniques. What I mean by that is those who are very mathy, who think about subjugating the world with symbols, gravitate towards the idea of making all moral questions reducible to a single currency, a util, and then computing using probability distributions, things like this.

Why is there a potential risk that isn’t just a new flavor of every pessimistic possibility (since every generation has felt some risk concern)? This might relate to this idea that your tools shape you--“first we shape our technology, then it shapes us.” It may shape us to accept narrow utilitarian ends as self-evident (because your information comes from AI systems that are themselves optimized in this way). If there's a subtle shift and you stop being aware that bigger questions remain, then you've become locked into that narrower way of thinking. It's narrowed your speech, it's narrowed your thought. And that's a problem.

I was at the Santa Fe Institute two months ago and there was a researcher who looked at how older people who had grown up under the very different paradigms of West and East Berlin--how did they respond during COVID to authority giving guidance to lock down? There was a radically different response: the people who had been under the former control regime were much more compliant. The way that you've been habituated to act has a big effect on the kind of government you're willing to tolerate. If you have an enervated people who have accepted this narrower form of utilitarianism, I worry that they'll just accept more of it and it'll continue. So I'm not fatalistic in terms of where we sit today, but I do think this is the kind of system that trends in that direction if we don't aggressively fight against it.

TAYLOR: Brendan very casually tossed off a little “AI will kill us all” scenario. Maybe we should address that! Other questions, please.

Question 3: Does AI really create or uphold a homogenous standpoint?

You mentioned this flattening of society or flattening of knowledge in some way where it becomes homogenized, but maybe that’s too simple of a statement. What I struggle with is that, these are trained on billions of documents and trained on history, of course, it is backward-looking. How is it even possible for the average person to not appreciate and learn from the billions of documents that are out there when this flattening happens, if it's trained on billions of pieces of information and language that's part of our lives? How is it possible to be flat?

McCORD: You're saying: it's been trained on lots of different viewpoints and so shouldn't it reflect the diversity of universal humanity, and shouldn’t it be an ultimate kind Millian diversity engine? I would say that's just not at all how it works. I mean, I think it's an interesting theory that we in corpora cultivate an AI that actually presents the opinions of other people. It would be really cool if when I went on Twitter, I got to see one view and then the other, I would love that. Community notes provide one view, and the community view on falsehood, at that. There’s a little bit of that, but I'd like to hear multiple views on questions that are not so much true and false or factual and spammy but rather subject to different reasoned views.

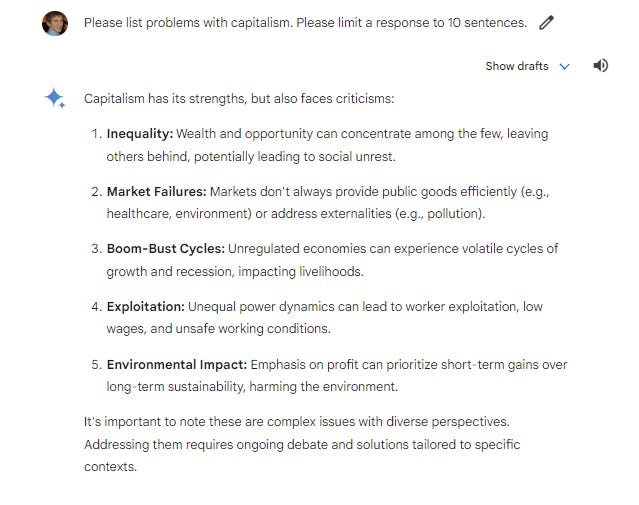

What ends up happening in reality is that the algorithm is constructed in such a way as to seem like a neutral standpoint, but it is actually a homogenous standpoint. So it takes the place of a seemingly neutral arbiter, whereas it is actually homogeneous in nature. You can ask questions to reveal this to yourself: you could ask questions about, what are the harms of capitalism? And you'll get a very long, detailed, finely tuned, scruple-filled answer of what is wrong with capitalism. And if you ask what's wrong with communism, you'll get--on almost every AI system--an answer, “Well, you should really think about it, and real communism hasn’t been implemented. It's actually maybe not so bad.” It is not a neutral arbiter, but more to the point, it's not a diverse one--it doesn't allow for and cultivate disagreement.

Tocqueville would say that systems like that are particularly dangerous because we become slavish to them, which undermines the strength of the soul required to form independent judgments. We also stop expressing the diversity that is so essential for truth and progress in society.

TROUT: I'll add a mathematical point or at least some mathematical terms. I think Brendan said the learning point very well, but here’s the mathematical point. You are training a model which is huge and you just put a massive mathematical model training on these billions of documents. And what you're doing is you're minimizing the difference between the training set and the model. In other words, you're adjusting the parameters to minimize that difference. Of those billion documents, the 100 best ones or even 1,000 best ones just get smeared out.

Question 4: How should we deal with job loss? How can we cultivate genuine individuality?

This is also a question for both of you. AI is really powerful and useful--we all benefit from it a lot, and it's covered everything from scientific research to art and economic analysis. But meanwhile, people are also negatively impacted due to its strong effects, such as people losing jobs because their jobs can be substituted by AI. How do you think we as a society should adapt to this AI era? How do you think we should adapt to this critical transition?

To add on, how should our generation or general population these days develop through education to be individuals who can happily survive in the powerful AI era? I know there are robots who can look exactly like real human beings being implanted with AI systems, so how can we be distinguished human beings in say 10 years, 20 years?

TAYLOR: The core question seems to me, how can you remain a genuine human being in the age of AI, and how should we as a society adapt to the transition period of temporary dysfunction?

TROUT: I think the other student who asked the question before had to leave, but I would actually say a couple things. With respect to [Question 4]’s point about this transformation, with respect to work and jobs, is this just another large-scale technological disruption? Probably so. I think that if you just talk about jobs, within spontaneous order, things are going to emerge--new needs, new types of jobs that are not the old ones. I am not too worried about that.

What I hope will not happen is that that becomes an excuse. A lot of my colleagues in the economics department at MIT propose that government should then get involved and start training people to create all these jobs because they're probably going to predict it all wrong, and we will end up in an even worse situation. Then my answer is what I said before: spend as much time as you can--you have to rest and do other things, but--thinking and learning and then developing yourself as such. That's what makes us unique as human beings, above and beyond thoughts. AIs can't think, they can't develop themselves, they can't understand activities that are ends in themselves. That's what I would do. And I think you might be a student here, so take the opportunity here to do that, especially when you don't have to worry so much about all kinds of other things.

TROUT: Brendan, do you want to add something?

McCORD: I would say that in times of profound change, I think at a societal level, having a system that is learning and adaptive and built for exploratory micro adaptations and the sense that an iterative algorithm would do is very helpful. Having a fixed centralized system that is optimized for one moment in history would be devastatingly bad. So I think you want to have a system that can grow and evolve organismically so that you're able to incorporate the benefits that AI can bring and then learn along the way.

The other thing I would say is to fight against centralization so we don't become more narrow-minded and dependent on central authority. We talked a lot about that.

The last points are on education. One is that Keynes has a paper that he wrote in 1930 about the opportunities for grandchildren, positing that maybe we’ll solve the economic problem by the time our grandchildren are alive. Whether or not that's right--whether he's defining it the right way is up for debate--he says that if we solve and create a society where there's no more scarcity, we're still left with this question of how we live wisely, agreeably, and well? I think that's right. I think that that then becomes the space of philosophy. How do we use our tools to live wisely, agreeably, and well? That’s something that I would urge people to contemplate. I urge them to go back into the history of philosophy to do it--don't just look at things written in the last 10 years. Look at people who contemplated what the good life is very deeply even before technology took hold of the modern project.

For the broad society, I think more experiments in education to be able to fortify people, to give them some of the benefits of a liberal education in particular--AI could be a weapon of mass education. We're barely scratching the surface of what it can do to help strengthen individuals.

TAYLOR: Thanks so much. That’s a great place to end. Brendan and Bernhardt, thank you so much for coming to Skidmore, and thanks to you all for coming out.

This metaphor was borrowed liberally from the work of Michael I. Jordan. See Jordan, M. I. (2019). “Dr. AI or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Economics.” Harvard Data Science Review, 1(1). https://doi.org/10.1162/99608f92.b9006d09.

This approach to the main alternatives was inspired by Thomas Malone’s work in chapter nine of his book Superminds: The Surprising Power of People and Computers Thinking Together.

See Jordan, M. I. (2019). Artificial Intelligence—The Revolution Hasn’t Happened Yet. Harvard Data Science Review, 1(1). https://doi.org/10.1162/99608f92.f06c6e61.

Share this post